For most of her life, Napolo from Narok County, Kenya suffered from eye pain. The 78-year-old first noticed the discomfort when she was in her thirties. She said it felt like there was always sand in her eyes.

Then her eyelids started turning inwards, causing more pain and irritation. She tried traditional remedies like plucking her eyelashes, but nothing helped. Her vision worsened over time.

One day, a community health worker came to Napolo’s doorstep to check on the family’s vision. Thanks to the primary eye care training we’d provided, the community health worker took one look at Napolo’s eyes and instantly knew what the problem was – a trachoma infection.

Trachoma is a bacterial eye disease that is a leading cause of blindness in areas with water shortages and crowded living conditions. The infection spreads easily through hands and clothing, and also through direct transmission by flies. If left untreated, trachoma forces the eyelid inward – like Napolo’s – making the eyelashes rub painfully against the cornea. Over years, it can lead to permanent scarring and irreversible vision loss.

The community health worker helped connect Napolo to our partner hospital for treatment. As Napolo was in the late stage of the disease, she required surgery. At our partner facility, the Talek Health Centre, she underwent an operation that corrected her inward-turned eyelids. The procedure brought her immense relief and preserved her remaining vision.

Stories like Napolo’s are an example of how we strive to address the root causes of avoidable blindness through a disease control approach. Our model helps us diagnose, treat and prevent the major causes of vision loss, including cataract, diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, trachoma and uncorrected refractive error.

Tackling trachoma through the SAFE strategy

Throughout Kenya, Ethiopia and Zambia, we’ve been working with communities and partners to eliminate trachoma through a four-step approach known as SAFE.

The SAFE acronym stands for:

- Surgery to treat trichiasis (the painful late stage of the disease)

- Antibiotics to eliminate infection

- Face washing and hygiene education

- Environmental improvement including wells and latrines

In Kenya, we work with government partners to distribute antibiotics to regions where trachoma is endemic. These antibiotics help prevent infection and can help clear up existing infections.

And because trachoma spreads quickly in areas where water is scarce, part of our approach is to make sure that people in our partner communities have access to a clean water source – by repairing and drilling water boreholes.

In the past couple years, we’ve focussed on training groups of local volunteers – called “Area Pump Minders” – in hand pump maintenance. That way, when a village borehole breaks down, someone in a nearby community will be around to fix it quickly. Throughout 2024, we hired on some of the Area Pump Minders we’d already trained to repair 129 boreholes – benefiting the nearly 130,000 thousand community members who depend on them.

Managing glaucoma one day at a time

Glaucoma is a tricky condition that often goes unnoticed until the damage is already done. Caused by increased pressure within the eye, it affects the optic nerve at the back of the eye, resulting in loss of nerve function and peripheral vision.

This often occurs painlessly, making it hard to detect. And any vision loss caused is generally considered irreversible. But if glaucoma is diagnosed early enough, it can be treated and managed with eye drops and medication, as well as regular checkups.

Ayetu, a farmer in Ghana’s Central Region, first noticed that he was having problems with his vision several years ago. After visiting the hospital, where he got a diagnosis of glaucoma, he started using eye drops. But finances were tight, and he found it difficult to pay for the medicine and attend his monthly appointments. Eventually he gave up and turned to herbal remedies, and when he did, his vision worsened.

In 2022, we started a community health project with the Winneba Municipal Hospital. Glaucoma patients with financial difficulties, like Ayetu, were told that their medication and appointments would be given free of charge – thanks to the generosity of donors.

When Ayetu found out he could get his medication once again, he felt enormous relief. He had worried about going totally blind, leaving his 75-year-old wife to manage the household on her own. Now, he says that the pain and tearing in his eyes has ceased, and the pressure has stabilized. “I was overwhelmed with gratitude when I started receiving these medications every month,” he says.

Retinopathy of Prematurity – a condition that robs children of their eyesight

Today, little Ayan and Vyan in India have a bright future ahead of them – but as infants, these twin girls narrowly escaped a life of blindness.

Born two months early in June 2022, the girls weighed just three pounds each and suffered from lung infections. They were rushed to a nearby Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) in their city of Moradabad where they were stabilized. While there, the doctor treating the girls recommended that they undergo screening for Retinopathy of Prematurity, also known as ROP.

Retinopathy of Prematurity, as the name suggests, is a condition that can occur in preterm and low-birth-weight babies. It causes abnormal growth of the blood vessels that attach to the retina, which leads to later vision loss if left untreated. It’s difficult to detect, and in the worst case scenario it can cause a child to go suddenly, irreversibly blind.

Since 2022, we’ve been working closely with our partners at the C. L. Gupta Eye Institute to screen and treat preterm infants throughout Moradabad and its surrounding districts for ROP. The Retinopathy of Prematurity Eradication Project runs a fully-equipped mobile screening van. A highly trained optometrist makes rounds of all the local NICUs, screening babies for ROP, treating simple cases and referring more complex cases back to the base hospital.

Little Ayan and Vyan underwent screening, and both were diagnosed with severe ROP. At just five weeks old, they underwent eye injections, followed by laser treatment. Now, thanks to regular checkups, their condition has been addressed, and the little girls can live up to their full potential with their vision intact.

These twin girls are just two of many infants that have benefited from increased ROP screening in their community. In 2024, we expanded the program to 28 NICUs in five districts across the region, enabling us to screen an additional 1,500 infants for ROP and provide treatment for 400 of them.

Putting futures in focus with prescription eyeglasses

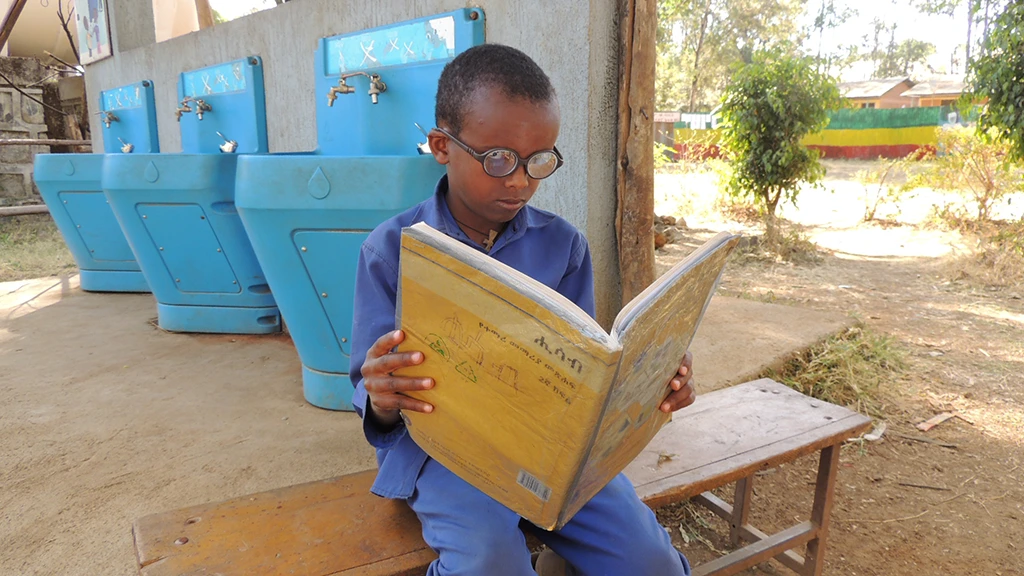

At just eight years old, Fassikaw in Bahir Dar, Ethiopia decided he’d had enough of school. His eyes were always watery, he couldn’t read the blackboard, he had to hold books just inches from his face and his grades were suffering as a result. He told his parents he wanted to quit.

His parents didn’t let him leave school, and when they heard about a school eye health program that was offering free diagnosis and eyeglasses to students, they jumped at the chance. They took Fassikaw to our partner hospital where they learned that he needed strong corrective glasses. Thanks to Partners in Education Ethiopia and our generous donors, he received the eyeglasses at no cost. Now that he can see, Fassikaw is finding school much more engaging, and his grades are on the rise.

What the little boy probably doesn’t know is that vision impairment like his prevents a lot of children around the world from finishing their schooling. In fact, children with vision loss are up to five times less likely to be enrolled in formal education in low-and middle-income countries, and a pair of glasses can reduce the odds of failing a class by as much as 44 per cent.

That’s why we help run school eye health programs, reaching children right where they need vision care the most – in the classroom. By training teachers and school health coordinators in primary eye care, we’re able to screen thousands of students in just days, quickly identifying those with possible vision loss for further referral. That way we can help more students like Fassikaw stay in school and thrive in life.

Adults, of course, also suffer from refractive errors, and sometimes providing a pair of reading glasses or prescription eyeglasses can change the course for an entire family. Take Junmoni’s story as an example. The mother of two in India helped support her family’s income by doing handloom weaving from her home. But as she got into her forties, she found it harder and harder to see the intricate patterns she was weaving. In despair, she was readying herself to sell off her handloom when she was surprised one day by a knock on the door. A visiting community health worker did a quick vision screening test and told Junmoni she likely just needed a pair of glasses. With a referral in hand, Junmoni visited one of our eye screening camps where she got a diagnosis and a pair of prescription bifocals all free of charge. Now she’s weaving again and saving up so she can send her young daughter to college.

We can provide eyeglasses to people like Junmoni and Fassikaw, with all associated expenses, for about $20 dollars apiece. In 2024, we distributed more than 270,000 pairs of eyeglasses – that’s a lot of lives transformed.

Addressing the global burden of cataracts

Across the world, more than 17 million people are blind due to cataracts, and cataracts cause another 34 million people moderate to severe vision impairment. But they are easily treated. A simple day surgery, one per eye – at the cost of about $75 Canadian dollars – can restore vision.

Despite that, millions around the world aren’t getting the surgery they need. The barriers are innumerable but usually include lack of financial resources to pay for the surgery, and lack of transportation to access the healthcare system. That’s why we work in rural, remote and underserved communities, identifying eye conditions like cataracts on people’s doorsteps and connecting them to the healthcare system – then ensuring that their treatments and transportation are subsidized or provided free of charge.

For someone like 85-year-old Esther in Kenya, a visit from a community health promoter made all the difference. Living in the remote village of Sitet, Esther struggled to get together the money just to visit the nearest hospital, let alone pay for the appointment.

About 10 years ago, when Esther was chopping wood, a log bounced up and hit her in the left eye. The pain was extreme, but she decided to wait and see what happened. A week later, in unbearable pain, she travelled to the hospital for help. There she received pain medication and a referral to an eye hospital. But by then, she was out of money. She went home and the vision in her left eye never recovered.

Three years ago, she started to notice the vision in her right eye was also fading. Soon, she could no longer manage her household, and her daughter had to move in with her.

“She had to leave her home to stay with me and help,” says Esther, about her daughter. “At some point, I just wanted to die… I didn’t want to hold her back from her life.”

One day, hope arrived in the form of a community health promoter who knocked on Esther’s door. The health promoter referred her to an eye screening camp, where she was diagnosed and referred for cataract surgery on her right eye. Unfortunately, the damage to her left eye was irreversible, making treatment of her right eye even more essential. As part of our program, Esther’s transportation, appointments and surgeries were all paid for, thanks to the generosity of our donors and partner, Johnson & Johnson.

Today, Esther is back to living independently – visiting friends, walking to church and picking and drying her own coffee beans.

Every year, the community health workers we train bring hope to thousands of seniors like Esther who once believed blindness was inevitable. In 2024 alone, community health workers helped us restore sight by making referrals for more than 230,000 cataract surgeries – giving people back their independence and dignity.

Seeing care through to the end

Our model offers patients the full continuum of care – from screening and diagnosis, through treatment, to follow-up. After surgery, our teams make home visits to check on healing, answer questions and make sure patients attend follow-up appointments. This helps us troubleshoot issues early and keep recovery on track.

For cataract patients, follow-up is especially important. When someone has cataracts in both eyes, we often schedule surgeries several weeks apart. That gap gives time for healing and reassessment, because the outcome of the first surgery can guide the second.

Eye surgery changes lives, but recovery looks different for everyone. By staying with patients through every step, we prevent complications, improve outcomes and build trust. When communities know we’re here for the long haul it makes our work more sustainable, with healthier futures for all.

Prevention is key to transforming lives

Vision loss doesn’t have to be inevitable. From Napolo in Kenya to Ayetu in Ghana and little Ayan and Vyan in India, these stories remind us that blindness can often be prevented or treated when care is accessible. Through community outreach, early diagnosis and partnerships that remove the financial and geographic barriers, we’re restoring sight and transforming lives. But the need is still great. Millions of people remain at risk simply because they lack access to basic eye care. Together – with continued support and collaboration – we can ensure that no one is left in the dark. Donate today to help us in our mission to prevent blindness and restore sight.