If you sprain an ankle or come down with a bad cough, your first stop is usually your family doctor. But when it comes to blurry vision, the path to care often looks very different. Around the world, eye health is still treated separately from primary health care, creating gaps that leave people without the vision help they need. Even in countries with universal health coverage, you might receive a complex eye surgery at no cost, yet pay out of pocket – or use private health insurance – for something as simple as a pair of eyeglasses.

At Operation Eyesight, we believe this needs to change. That’s why we’re working to strengthen areas of overlap between primary eye care and primary health care in our countries of operation. That means supporting the World Health Assembly’s integrated people-centred eye care (IPEC) resolution by working to integrate eye health into national health systems – and increasing access to free or subsidized eye health care.

It also means addressing the root causes of avoidable vision loss. In some regions in Africa, we bring fresh water and hygiene education to communities to help prevent infectious eye conditions. We also work to make sure our services offer more than just eye care, but can also link patients to other types of health care.

Why eye health can’t be treated in isolation

Health conditions rarely exist in silos – and vision loss is no exception. Diabetes, for example, increases the risk of eye conditions like cataracts. For 15-year-old Vanessa in Zambia, blurry vision was one of the first signs of the disease. When she started having problems reading the blackboard at school, a teacher sent her to our vision centre in her community of Matero for a checkup. From there, she received a referral to our partner hospital, where she learned that she not only had cataracts, but diabetes as well. Doctors helped her get her blood sugar levels under control, and then she got cataract surgery. Today, she is managing her diabetes and thriving in school, with dreams of becoming a doctor.

Vision problems can also cause a downward mental health spiral. Benson, a farmer in Kenya, lost his ability to work due to poor vision. As a result, he became angry and depressed, then turned to alcohol and drugs to cope with his situation. Luckily, his family got him into a drug and alcohol rehabilitation facility, where a visiting doctor diagnosed him with cataracts. Benson underwent surgery on both eyes, provided free of charge thanks to the support of our donors, and can see clearly now. Buoyed by his miraculous recovery, Benson finished up his time at the rehabilitation facility and happily threw himself back into farming.

Integrating eye care into Canada’s health system

In Canada, where Operation Eyesight is based, navigating eye care can be confusing. While the Canada Health Act covers medically-necessary eye health services, routine vision care like eye exams and prescription glasses often isn’t part of the deal. That leaves provinces and territories to fill in the gaps, and the result is a patchwork system. For example, seniors in Ontario get routine eye exams covered once they hit 65, but in Newfoundland and Labrador, those same seniors might have to pay out-of-pocket. It’s inconsistent, and it’s especially tough on vulnerable populations.

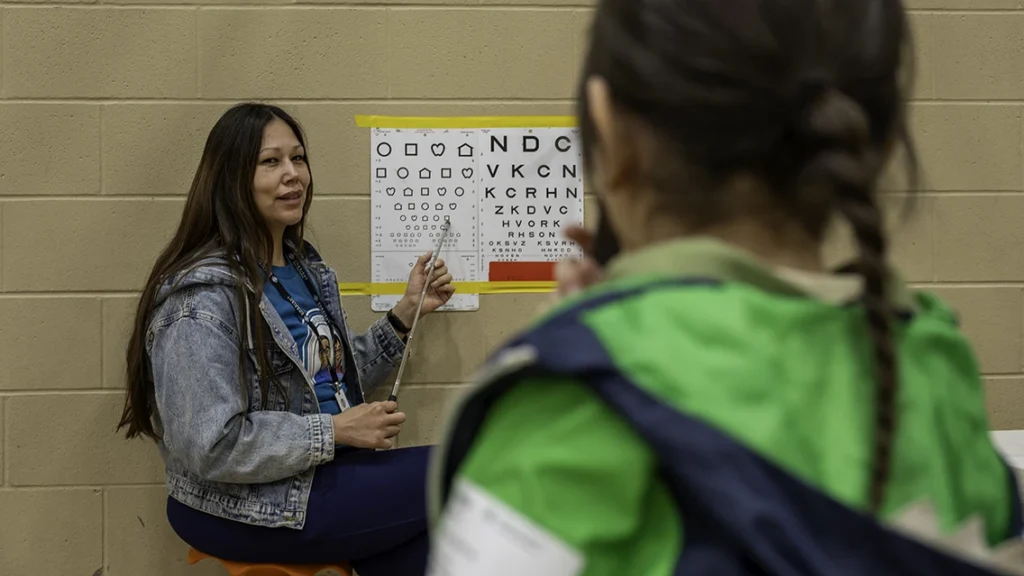

There is some support through the Federal Non-Insured Health Benefits (NIHB) program, which covers eye exams and eyewear for eligible First Nations and Inuit individuals. But even that has its hurdles: remote communities, limited healthcare infrastructure and cultural differences that make accessing care more complicated than it should be.

The passage of the National Strategy for Eye Care Act in 2024 was a major step forward in addressing these issues. As chair of the Canadian Eye Health Coalition, Operation Eyesight is helping shape a national framework that prioritizes equitable access to vision care. Our Global Director of International Programs, Kris Kelm, explains why it’s important that we have a seat at the table during the consultation period and beyond.

“We know that there will be many voices in this conversation with diverse interests, and we want to ensure there is representation from patients who have the least means and the least ability to access vision care,” he says. “The fact that we have over 60 years of experience working in this sector gives us a strong background to speak credibly to how we need to approach things in Canada, and our community partners can provide valuable insights to help shape eye care for all.”

He adds that Canada can learn from some of our countries of work, where eye health has been better integrated into the overall health systems and other public frameworks. As an example, he points to Ghana, where we work with the ministries of health and education to screen and treat students for eye conditions in the public school system. We have similar programs in Kenya and Zambia, too.

Another example is in India, where we are working with state governments to establish vision services in pre-existing government health centres. Building the capacity of vision care facilities within the country’s national health care system ensures that services reach the most underserved populations, as patients who are able to pay most typically seek care at for-profit facilities, rather than attending government services.

Community health workers: Integrating eye care at the community level

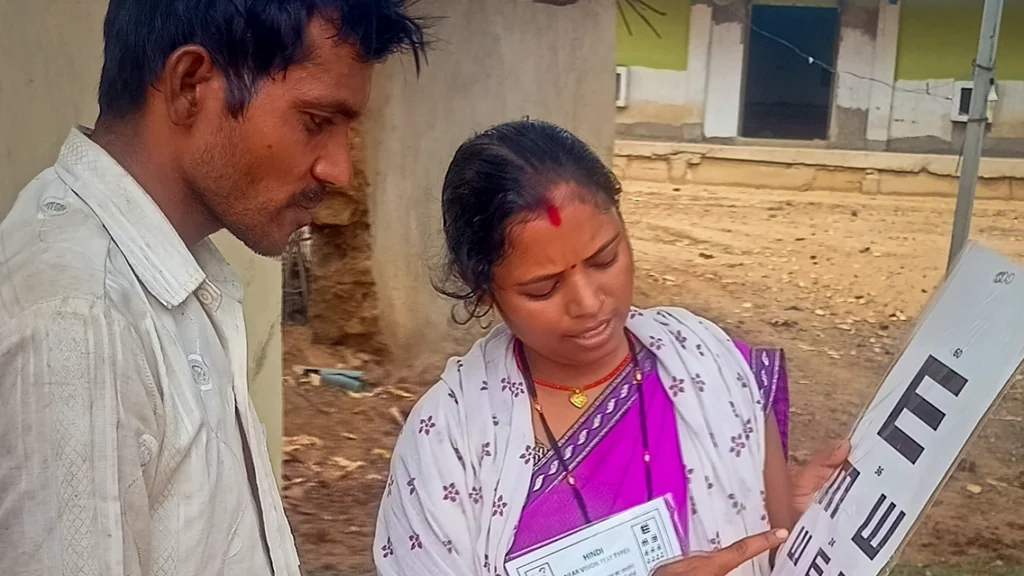

Shakuntala, in Madhya Pradesh, India, spends her days walking door to door through villages in her region, checking in on the health and well-being of families. She’s one of the million-strong network of Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs), employed by the Indian government, who deliver primary health care at the community level.

Her work includes providing pregnancy advice, supporting newborn care, educating parents about vaccinations and vitamins for children, and making all kinds of referrals to local clinics and hospitals. In 2022, Shakuntala added another set of skills to her toolkit: conducting primary eye health screenings, thanks to training provided by our Operation Eyesight team, in partnership with the Government of Madhya Pradesh. Shakuntala learned to measure visual acuity using an eye chart. She also learned to identify the signs and symptoms of various eye conditions. Once she identifies a patient with a possible eye condition, she refers them to the base hospital for diagnosis and treatment. In the meantime, she continues to provide advice and referrals on nutrition, vaccinations, prenatal care and other health concerns.

Shakuntala is just one of the thousands of community health workers we work with across the globe. In all our countries of work, we partner with existing health systems to recruit community health workers, mostly women, to help us deliver our programs. The health workers develop strong ties within the communities, resulting in high acceptance and trust in our programming.

Mabel, a community health nurse in Ghana, was trained in primary eye care so that she could identify eye health issues in addition to her regular duties. She says that being able to screen people at their home allows her to reach many women and girls who probably wouldn’t have left the village to seek eye health care, due to household responsibilities.

Water and WASH for sight

Anyone who has had a case of pink eye knows that having red, inflamed and itchy eyes isn’t much fun. But in some parts of the world, an eye infection can be a much more serious problem. Trachoma is an infectious eye disease that leads to vision loss and blindness in millions of people across the globe. It spreads easily through contact with eye discharge from infected people on hands and clothing, and through flies. If left untreated, chronic infections turn the eyelid inwards, causing intense pain and scarring of the cornea, which can lead to irreversible blindness.

Trachoma is preventable, and clean water is key to curbing the spread. When communities have access to clean water, people can clean their hands, faces and clothing more often, which prevents it from spreading.

In countries like Zambia, we work with Water Affairs (the government department responsible for water) to drill, rehabilitate and repair boreholes near where people live, work and go to school, so that whole villages have access to clean water. We also provide training to local volunteers in these communities in WASH (Water, Sanitation and Hygiene) and borehole repair and maintenance to ensure the clean water continues to flow. In areas where trachoma is endemic, we also work with partners to distribute antibiotics, which both treats and prevents trachoma.

It’s another way that we work to address one of the root causes of avoidable vision loss, but it also helps us tie into improved health outcomes overall. Accessible clean water helps prevent dozens of infectious diseases. It also improves quality of life for women and girls, who are often tasked with the job of fetching water, which can take up hours out of the day and prevent them from participating in school, work or other activities. Moreover, clean water means people can grow vegetable gardens, raise livestock and keep entire families, and communities, happier and healthier.

Tying it all together

When we invest in sight, we invest in education, productivity and dignity. To eliminate avoidable vision loss, vision care needs to be recognized as a public health priority and integrated into national health strategies. Operation Eyesight’s global experience – from rehabilitating boreholes in Zambia to collaborating with partners on new policies in Canada – demonstrates that integrating eye health into primary care, addressing environmental determinants like access to clean water, and empowering community health workers leads to sustainable, measurable outcomes. Policymakers have a critical role to play in building resilient health systems that ensure equitable access to vision care for all.

Read more about our approach to Hospital-Based Community Eye Health.